Why a Half-Life Comic?

There is never a shortage of original ideas, whatever they may be.

When Mike and I first decided to produce A Place in the West, we’d been thinking about comics on and off since 2009. We had previously been developing our own sprawling science-fiction saga that we (erroneously) believed would comfortably see us through the next several years. It didn’t seem to enter our minds to ask whether we’d be any good at it, given that we’d never written a comic before. It seemed to us that our love for the medium would guide our hand, and in a way, that’s exactly what happened. But being a fan is one thing - producing that self-same thing is an altogether different beast! With our sprawling sci-fi saga roughly mapped out, we’d start writing those scripts (or, more accurately, script; because why bother with manageable issues when you could write out all 1,000 plus pages in one go? Psh, issues...), hire an artist to start drawing, and away we’d go.

For all kinds of reasons, many of which I’m sure you can guess, that’s not what happened. I don’t remember when exactly, but it eventually became apparent that we had no idea what we were doing and that we were far removed from our comfort zone. If we weren’t careful, we were going to destroy our story with a deadly mix of inexperience and ineptitude. We’d envisioned the story as a comic book story - that was our chosen medium, and no other could accommodate it. But that intuitive belief doesn’t necessarily translate into a practical ability! Inevitably, we found ourselves struggling with the scope of the story, and we couldn’t properly express our ideas on the page.

This was all very frustrating. It was clear we had to start experimenting, but this wasn’t the story to do that. The saga in question was something we’d come back to a few years down the line. We needed something smaller, more manageable to work with; something that would help us find our voice as we navigated the world of comics.

It might seem obvious you’d need to cut your teeth on something smaller first, but honestly, it just didn’t seem that way when we were younger. I guess it never does. This realisation led to the birth of A Place in the West. We needed to be less ambitious, to be realistic about the kind of story we could accomplish with our limited finances, and be honest with ourselves about our abilities. As I said to one interviewer at the time of the first issue’s release, “We needed to know if we could actually put together a comic and make it work. Can we tell a story and do it well?” Three years later, we now know we can indeed put together a comic and make it (mostly) work. Can we tell a story and do it well? I’d say our success in that regard has been substantially lower, but I’m getting ahead of myself...let’s go back to 2013, where two naive younger writers decided a Half-Life comic was their way forward.

Up until then, the comics of the Half-Life universe had been exclusively fan-made Garry’s Mod productions, the quality of which varied widely, reaching its zenith with the superlative and witty Concerned by Christopher C. Livingston. And whilst Valve had broken into comics with their other properties, from Left 4 Dead, to Team Fortress 2, and even the Portal franchise, they had yet to do anything with the Half-Life property outside of video-games (although at this point, it had been a very long time indeed since we’d seen a Half-Life anything, video-game or otherwise). And so, in our eyes, the space for an expansion of the mythology was growing larger and larger, and we were determined to fill it.

The hugely successful and consistently funny "Concerned".

It wouldn’t be the first time. Ever since Half-Life 2 launched in 2004 and changed the face of gaming forever, myself and Mike had been dipping in and out of its creative universe. At this point we were working more-or-less exclusively in the modification scene. There was something so alluring, so appealing about this bizarre, pulp science-fiction adventure that was unlike any other AAA title. The story of a legendary scientist-turned-resistance fighter who must pit his wits against a malevolent multidimensional empire, one he himself had inadvertently unleashed upon the world over a decade ago, was vast and weird, brought to life by an extraordinary cast of characters.

The ambiguity of Valve’s narrative and their piecemeal approach to world-building teased a universe far greater than what we experienced within the strict time frame of the games themselves. What exactly did the world look like outside of City 17 and its immediate environs? And what kind of adventures were taking place out there? And who was having those adventures? All of these world shattering events - the Black Mesa Incident, the Combine occupation - how were they experienced by characters not directly plugged into that larger mythology? Each time Mike and I returned to the world of Half-Life, it was these questions that compelled us.

To help you understand the process by which we settled upon the story of A Place in the West, let’s take a brief look at those that preceded it...

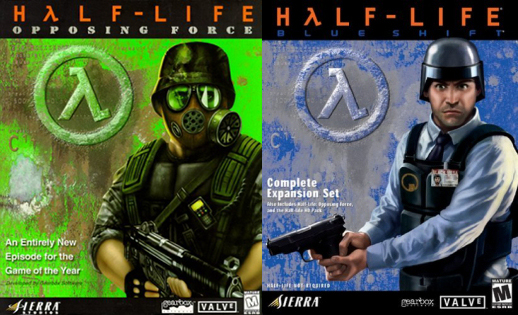

The first idea came directly off the back of Half-Life 2, when I was 13. I wrote a story that took place during the week in which the uprising against the Combine began, and called it (yeah, yeah) Dark Awakening. Gordon Freeman's incursion into the Nova Prospekt prison liberated the player from their confinement, and they were quickly swept up in the ensuing rebellion. It was very much in the vein of the original expansion packs, like Opposing Force and Blue Shift, designed to fill in the gaps of the Half-Life story, rather than explore new territory. This falls roughly in line with how many expected Valve to continue the franchise. There’d be a significant break between Half-Life 2 and the next Freeman-centric installment, with expansion packs filling the interim. It’s what happened before, it seemed likely it’d happen again. Valve, of course, had bigger, more ambitious plans, but I’m getting ahead again...

"Opposing Force" and "Blue Shift".

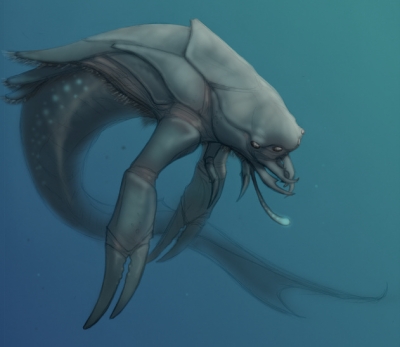

Not only was Dark Awakening far too big to be realised, but it was apparent in the storytelling that these core aspects of the Half-Life story were for Valve, not me, to tell. I was also 13, so even with the generous aid of other modders, I’d conceived of gunk like a transhuman colonel with a synthetic arm and a weird Combine factory inexplicably called “the Ventacon”. I don’t remember what it was for (maybe it was a boring riff on the scrapped Air Exchange facility?), but I do remember it was to be powered by huge alien sea monsters hooked up to underwater generators. The player would have to take these offline by killing the monsters, thus destroying the Ventacon. It was fun to be 13 (I still have the concept art for it, and a broken bsp. file, which are credited to the very talented “Mechagodzilla” and “Jandor” respectively).

Oh, here it is. The Brazas. Geddit.

Not to be deterred, I soon met my future writing and business partner, and best friend, Michael Pelletier. He too was keen to get into Half-Life (or maybe I convinced him…), and together we came up with Krasota Razbrosanaya: The Scattered Beautiful, which is hands down the worst title ever (not worse than "Dark Awakening" - Mike). It took place in Leningrad (renamed from St. Petersburg to emphasize the idea of resistance immortalized in World War 2’s sieges), and there was the idea that a group of mostly Russian resistance fighters would strike a powerful blow against the Combine by depriving them of one of their power bases. This was around the time - circa 2005 - that Valve announced their intention to explore the as-yet uncharted territories of episodic content. Half-Life 2: Episode One had been released, and we’d been bitten by the episodic bug, too. We planned for four episodes that would take players roughly 12 hours to complete. Interestingly enough, vague slivers of ideas developed during this period would survive long enough to materialise in A Place in the West. This included the winter setting and a church-as-refuge locale. The character of “Clarence Headway” would not would survive the passage of time, nor indeed would “Henry Ledbecker”. Their fate remains unknown, and at least one of us hopes it stays that way (spoiler alert: it’s Mike).

Screenshot from an early WIP map. There is a direct reference to this stairwell in the first issue of the comic!

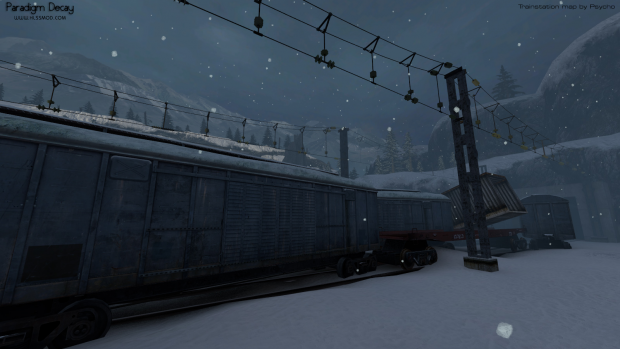

KR failed, too. Thankfully, we did not have the resources to do justice to our ideas. But we were not done! We still wanted to make a Half-Life game! We would not be stopped (we would, thank God). We took the one part of KR that didn’t suck - our protagonist, Mika - and transplanted her to a Siberian setting that would come to be known as “the Region”, and called our next venture Paradigm Decay. Reflecting on KR’s failure, we figured that perhaps 4 episodes was too ambitious for a small group of fledgling game designers, and so we scaled it down to 3 ... like it was that one additional episode that had held us back. We never seemed to come to terms with the fact we utterly failed to get even one playable episode of the last game shipped, let alone a sequel! And it’s not like the sequence was Dark Awakening, Krasota Razbrosanaya and then Paradigm Decay. There were numerous failed modifications in between not related to Half-Life (they were all original titles that required a ton of custom assets).

The first map - Train Yard. The map’s designer, Aaron Garcha, would return to design the background for our app.

With Paradigm Decay, we were intent on creating a story of unchecked scientific power, legacy and responsibility, and unexpected heroism...so, a Half-Life story (this project is best described as LOST by way of Half-Life. So much ripping off occurred). It climaxed with an assault on a Combine-controlled science station. Fighting alongside the player were GIANT ROBOTS (think those bipedal mechs from Metal Gear Solid 4...the ones that moo. Like a cow). We built most of the first episode, and it was playable from start to finish. Unfortunately, as it became harder and harder to implement the talkie scenes, the team drifted apart and the project was abandoned. We never got to see those robots.

In retrospect, these were some of the best and worst years of our creative lives. That our trajectory in that field was doom-laden is beside the point, in a way. It was an incredibly fertile period of creativity, and our imaginations went wild with Valve’s world. We were learning so much, even though we weren’t totally aware of what those lessons were at the time. Obviously, a lot of this is related to age and experience, but there were others who succeeded where we didn’t, and that’s because they had a stronger understanding of the field they were in - video-games - and what they could feasibly accomplish there. We watched a lot of talented, amazing people do great things with the smallest amount of resources. We were going too big, too fast...and if we were honest with ourselves, we were in the wrong game. Yes, a pun.

Mike and I were creating these big, character-centric narratives, whist simultaneously telling designers how to design, what to design, and so on (don’t be that person). We were just these two overbearing obstacles for designers to contend with. We wanted more collaboration and we wanted the designers who worked alongside us to take their own initiative, but we didn’t have the skills to foster that kind of environment. We were our own worst enemies. So, we removed ourselves from the process until we could better understand our creative desires and what we wanted to accomplish by telling stories...yeah, we wanted to be storytellers, but what was really driving that? What kind of stories did we really want to tell?

In 2009, our lives underwent radical changes in circumstance, which lead to a stronger understanding of ourselves as writers. The details of these changes are rather personal and extensive, and so best left for another time, but suffice it to say, I was about to leave adolescence behind. The outcome of this was the realisation that we really, really wanted to write comics, and it became feasible for us to do so. The sci-fi saga we had planned strongly reflected the political and socially conscious writing we wanted to explore, but it was felled by a vein of overreach not too far removed from our previous experiences.

This didn’t happen overnight, though. We spent a good three years writing, writing, and writing, before facing the hard truth: we’d never get anywhere in this business if we didn’t start illustrating our scripts. This step was a surprisingly daunting one! As we explored our options, we begrudgingly accepted that unnamed sci-fi project would not be our first comic. It was disappointing at first, given we’d worked so intimately on that world and its characters. But they were not gone, and we’d return to them when the time was right.

In the meantime, we needed a story, and Mike asked if I had one... I pitched him a bare-bones Half-Life story. Kidnapped children. A damaged father. An intrepid young scientist. Missing Citadel. Isolationist military enclave. Big, purple tentacle thing. He suggested we set it in America, and wanted to dig into New England’s rich history. That excited me – the combination fit. So, we sat down and started fleshing out our characters. The story of Leyla Poirier, Albert Kempinski, Sejal Rajani and Long came to us very quickly, and they became our representatives for a new kind of Half-Life story.

Suddenly, we had our comic.

One of the things that constantly held us back during our video-game phase was not having the resources to make the things we’d dreamt up. We didn’t have the budget of a AAA developer. Or of a humble indie developer. We...didn’t have any budget. So, we couldn’t pit the player against, say, a Gonarch, because we’d have to model it, texture it, animate it, code it…yeah, not going to happen! At least, not by us. There are some incredibly resourceful people out there with the skills and the talent to make that happen. Mike and I were not those people. We were ideas people; we could write stories and produce design documents all day long. But when it came to the production of actual stuff, of models, of textures, of maps, of code, we had to rely on other people. Take Half-Life Short Stories: Human Error, for example. This was a modification largely mapped, modelled, animated and even voiced by its creator, Tero “Au-Heppa” Knuutinen. He involved himself in almost every aspect of production. Instead of relying on someone else to create new enemies for him, he made them himself! He actually produced Human Error alongside Paradigm Decay, and we were both amused and awed by Tero’s ability to bring his imagination to life. We hadn’t even left the starting line.

Son of a bitch made his own goddamn GRUNT ("Human Error").

Meanwhile, there were those modders doing very cool and exciting things with the existing assets, like Adam Foster and MINERVA. And again, he was able to create that himself. Mike and I might have been able to do this if we’d properly applied ourselves - perhaps Mike more than I - but we were honing a different set of skill sets. Besides, we didn’t want to take a minimalist approach to the storytelling and deliver exposition by way of radio or text. We really wanted to create our own living, breathing characters you could interact with - people who said just as much through their facial expressions as in speech. After all, wasn’t that one of the best aspects of Half-Life 2?

With A Place in the West, we can do that. We can create a cast of (hopefully) compelling, complex individuals and place them in (hopefully) all kinds of cool settings and conflicts. We wanted a Gonarch, and so we included a Gonarch. For us, Valve’s world was this enormously wonderful toybox we could only play with some of the time, and only with this thing, and not that one. That is no longer the case. As we progress with A Place in the West, you’ll see us embracing the medium more and more and finding new ways to visualise the world of Half-Life. Creatively, it’s just so exciting.

We weren’t done with Half-Life, and it wasn’t done with us. We know our work is different, and we know it might not be what you’re expecting from that world. Maybe those game ideas I described are closer in spirit. But hopefully you’re willing to come on this journey with us, because as much as we want this story to be our own, it is one-hundred percent the work of two die-hard lovers of Valve’s world who have spent a very long time immersed in it.

And the best... well, that’s yet to come.