Memory of the Future

Spoilers for Half-Life: Alyx. Just titanic spoilers, all the way.

Oh, and fair warning: this is a long, discursive deep dive into Alyx, and it may not have the strongest through-line.

TREPIDATION, ANTICIPATION

Valve are very precious about their Half-Life IP. It’s a right they’ve earned by turning nearly every instalment into a candidate for one of the best games ever made. The purpose of a Half-Life instalment, it seemed, was to change the nature of the game - literally. But back in the mid-2000's, Valve had committed to experimenting with an episodic model for the series - smaller, bite-sized chunks of gameplay intended to mitigate long development cycles. Ironic, then, that this same commitment would precipitate the biggest gap between releases. By their own admission, once Episode Two concluded Valve's plans for the climactic third chapter could not be fulfilled by the episodic model. Consequently, Half-Life was put aside for a decade (give or take a few wild ideas that never took off). So if they were getting back into the Half-Life business now, they were evidently confident in whatever it was they had found in Alyx, and were eager to share it. I like Valve’s approach to storytelling and game design, so it stood to reason I ought to be filled with anticipation for what was coming. It’s one of the reasons I’m living the creative life I always wanted to. And yet in the couple of months that followed the announcement trailer that’s not really what I felt at all.

It’s now an occupational hazard for me that a new Half-Life game is a source of trepidation, not anticipation. I realise that’s something of a self-inflicted injury, but it’s just super hard for me to disentangle the series from our own little slice of Half-Life we’ve got going. That doesn’t disappoint me per se – I like our comic quite a bit – but it’s odd in that it’s such a starkly different response to the one I’d have had five years ago. Further, I wasn’t sure I was even going to be able to play Alyx. But then it came to a week, maybe two before the release, and I just couldn’t help myself – the anticipation had taken hold, and I suddenly found myself pretty excited about the whole thing (it helped that my friend had kindly let me use their Oculus Rift for a few weeks).

Alyx is a game that came out of nowhere. Utilising a technology I admired but little understood, it would unfold from the point of view of a character I cared about a lot. That was kind of a big deal, and at the last minute I was fortunately able to put aside any fears I had of the game trampling over the canon (a deplorable word) we’d embraced to tell our story and just see the game on its own terms. As something to be enjoyed. ‘Cause writing fan fiction, officially licensed or otherwise, sort of implies you’re a fan, and what a shame it would be for me to forget that.

And really, I still had no idea what to expect from Alyx. Well, it's been out for over two weeks now, and I’ve played through it twice, with a third playthrough on the horizon (that gnome ain’t gonna carry itself to the Vault now is it).

So. Half-Life: Alyx. There’s so much to say about it that I’m not at all sure where to start.

I recently wrote an overly long piece on Alyx Vance herself, and upon finishing the game a follow-up presented itself. There is so much to say about how they’ve developed the character, about virtual reality’s potential for expanding Valve’s empathetic frontier, and about that ending, in which memory of the future did indeed play more than a passing role. Memory of the future – an unforeseen consequence.

The unforeseen consequence.

But for the moment, let's just park the Half-Life of it all. The sheer visceral experience of inhabiting this vast sci-fi world in VR, of interacting with it and knowing that with each step or jump you take you’re witness to an incredible watershed moment in gaming, is pretty unforgettable. Alyx is a triumph.

Right now, I think the instance that stands out most is from watching my housemate play the game. Like a lot of gamers he has real trouble looking up, and it was strange to see him miss so much of his surroundings when I’d struggled to move from one location to the next, so absorbed in what I was seeing all around me. I’m generally loathe to interrupt someone’s playthrough or act as backseat gamer, but as he approached the entrance to the Quarantine Zone, tunnel vision the whole way, I couldn’t help but suggest that, maybe, he should look “up.” So, he stopped, craned his head back, and uttered a little "oh."

A monolithic bastion of Combine smart walls towered before him, clasping the marred remnants of a European metropolis beset by two different kinds of alien life – a fungal infestation growing from within, and the brutal, technocratic regime determined to contain it. He then raised his arm and removed the hard hat from his head. It was a comical bit of affectation, inspired by a genuine sense of awe at the game’s scale.

A moment only possible in virtual reality.

IT’S BIG. REALLY BIG

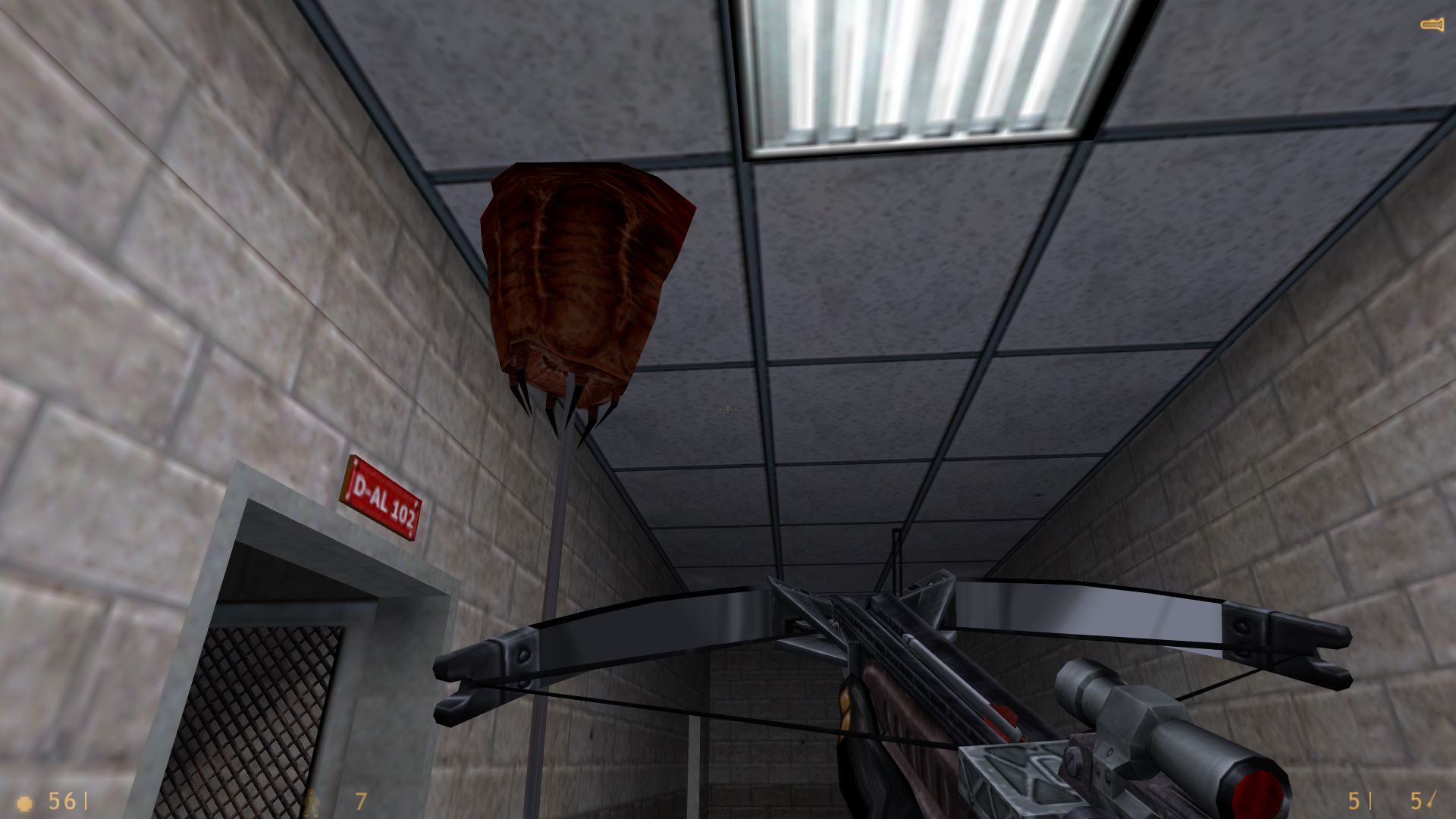

And that’s because Alyx is a big, big game. From the headcrabs to the Combine soldiers, each part of the world is properly scaled, giving it a weight, scope and dimension rarely seen in gaming. It might be that I just don’t play enough VR, but just when I thought I’d never be surprised by a headcrab or barnacle ever again, Valve asked me to hold their beer.

A month or so ago I ran through Half-Life 2 and its sequels, leaving commentary for each chapter on Twitter. It was a good time, but I’ve played enough of them now to know which parts work for me and which parts don’t. By the time I reached Episode Two’s third chapter – Freeman Pontifex – I’d honest to God had it with zombie gameplay. There was no variation to these encounters Valve could provide that would pique my interest, and subsequent chapters only doubled down on this truth. It was my feeling that even Valve had lost interest in them, as if the developers were just going through the motions. They were probably just as eager to leave City 17 and its surroundings areas behind, even as it strained the episodic model they’d committed to.

I mean, it’s not like headcrab zombies were going to move the medium, or even the genre, forward in the way Valve might have aspired to.

I’ve now handed back Valve’s beer, and I sit here thinking of all the ways in which hours of side-stepping and shooting headcrab zombies consumed my first week in lockdown, and how best to enthuse about it in writing. Zombies are hulking monsters of flayed flesh and exposed organs, lashing out at you with clawed appendages; they feel and look grotesque, and you’re not going to want them anywhere near you. They’ve always been gross, but here they are repulsively tactile.

The headcrabs sucking at their craniums are bulbous nightmares just waiting to leap out at you. If you aren’t accurate enough with your shots, they’ll disembark from a downed zombie and come crawling towards you, and in VR that’s not something you want. Like, at all. It’s like being Jeff Daniels in Arachnophobia, clumsy and terrified, throwing whatever you can get your hands on – bottles, chairs, anything (not the Chateau)– to keep ‘em at bay. And they’re so physical, too. If they miss you when they jump they’ll likely hit something, bounce off it, and then roll around on the floor trying to right themselves, just as you desperately release the empty clip and try and slot another one in.

Except you’ve forgotten to release the safety. It leaps at you again, this time gripping your chest. Frantically, you hit the catch, twist your arm, and fire.

This will happen many, many times, and each one will be no less freaky than the last.

Similarly, barnacles are a more prominent threat than before, and are themselves a truly carnal presence. They growl, gurgle and twitch, and a disproportionate amount of my playtime was spent studying them.

Alyx spends a lot of its first several hours in their company, which is just as well because acclimatising to VR combat isn’t easy. At least, it wasn’t for me. Given the way in which Valve chose to pace the game, I assume that’s true for a lot of players. The first encounter with zombies is very carefully set up: they block your passage and to progress you must engage them, but the manner in which you do so is up to you. They won’t actually attack until you enter the area, meaning you can see them and adjust before you take the next step. So much of the game is like this, and you won’t face enemies that fire back until much later. Even then there’s a substantial gap – a chapter and a half, maybe – before the second or third engagement.

The game progresses slowly and deliberately, careful not to overwhelm players and hyper conscious of the medium it’s taking place in. I never felt unprepared for what was ahead of me, and Valve’s design seemed to reflect my own trajectory through the world. So much time is given over to learning the ropes that it leads to a very different kind of Half-Life game. In a way, the nature of each encounter reminded me a lot of Episode One’s first chapter, Undue Alarm. In that chapter you’re only equipped with the Gravity Gun, and there’s a steady elevation in threat from one sequence to the next, but it felt contained and manageable. Alyx is a bit like that, but for hours at a time.

It’s a smart move that readies you for an intense final stretch, but I also feel like the game’s first phase of environments (sewers, tunnels, subways) outstayed their welcome sooner as a result. In VR, you don’t whip through environments blasting away enemies at breakneck speed. You take your time because, depending on your settings, your movement is truncated and deliberate, rather than quick and breezy. Valve have created a rich, detailed, sumptuous world you’ll want to explore, one that rewards you for exploration. But I eventually tired of the dark, industrial mire, and there were points where I felt fatigue and a longing for sunlight. In games past, Valve would have anxiously provided me with that, but there’s a sense that they weren’t able to do that here. I knew the game had been slowed down for my sake, and whilst it’s a decision I understood, I couldn’t help but be frustrated by it at times.

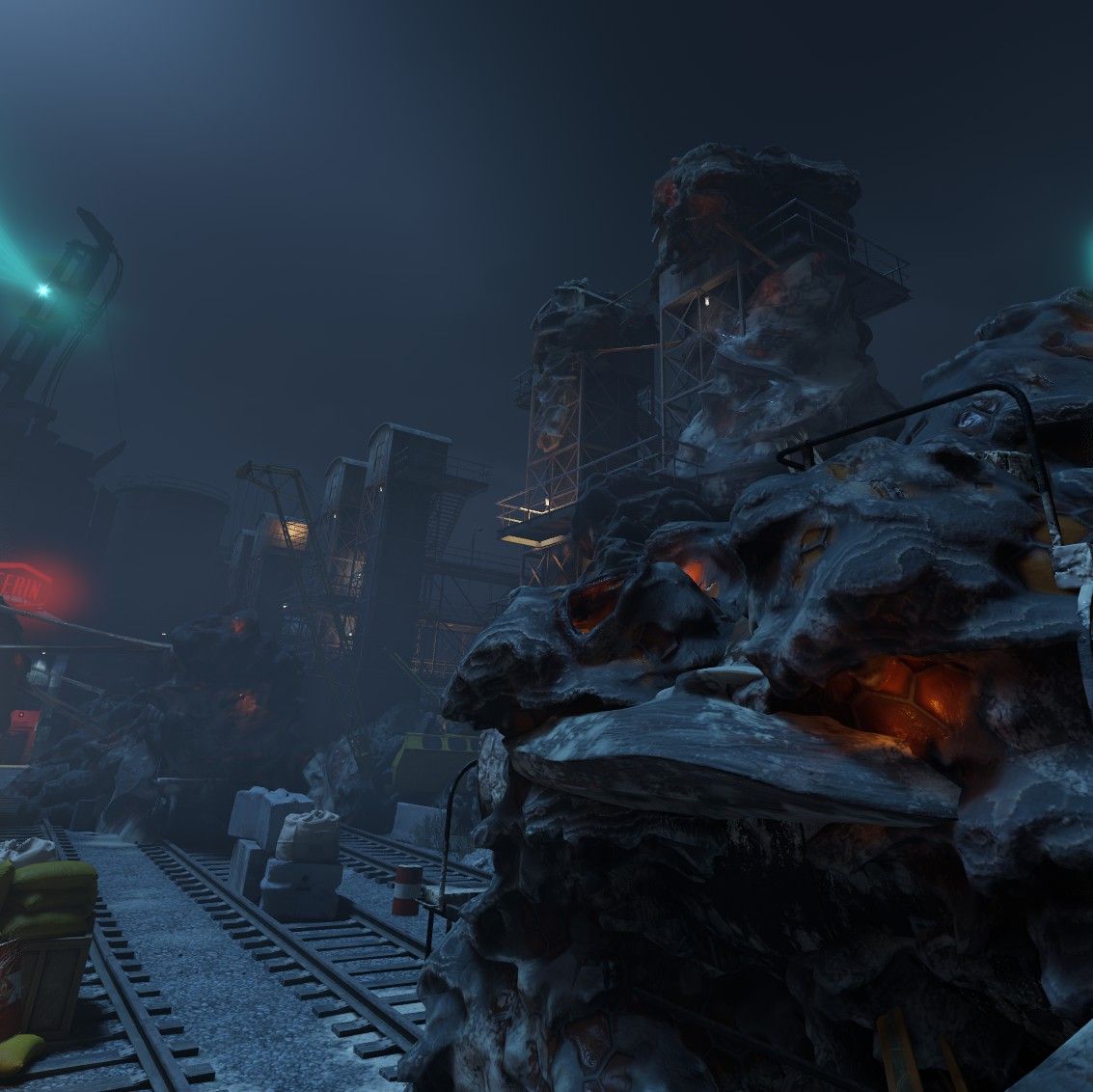

That frustration evaporated by the time I left The Northern Star. The latter half of Alyx is a masterclass of design, banking on all the skills you’ve learned so far to see you through a succession of intense, white knuckle showdowns with the Combine Overwatch. In one late stage sequence, antlions – humongous, just humongous alien bugs– stalk you through an ooze-coated train yard, Combine soldiers firing at you from platforms above. It requires dexterity and quick reflexes to traverse, and it ranks as some of the most enjoyable combat I’ve ever experienced. In many ways it’s more akin to the combat of Half-Life and than Half-Life 2.

At one point I took temporary shelter in a hut, hastily extracting the health canister from my glove and pushing it into a charger station. Bullets peppered the window as I pulled the lever, and I could hear antlions closing in. As the little needles did their work on my hand – no small task, given I had half a heart left – I turned my head, pointed my pistol at the door, and blew away the antlion charging towards me. Pistol ammo depleted. Nearly three full hearts, but not quite. A second antlion came into view, and I went to switch to my shotgun, cursing the charger’s speed...only to see that the antlion had lost both legs, and was struggling past the hut, mostly harmless. I relaxed, and lowered my arm. Full health.

The emotional highs of that experience are hugely amplified by VR. I didn’t require a further justification as to why the game had been built this way, and for such a small fraction of the fan base, but it felt like the moment I really understood what Valve had accomplished. They’ve set the bar and they’ve set it high, and I think it’ll be some time before another rich developer has the nerve and audacity to meet it.

Beyond that, there’s so much more to love. The Gravity Gloves, for instance, are ingenious; a contraption that’s so Valve in nature, executed with simple sophistication that makes using them to interact with objects a thrill. Pointing at an object, flicking your wrist, then catching that object in your free hand is deeply satisfying. Which is good, ‘cause most of the game is going to be spent doing just that.

Equally, I really appreciated the increased level of interaction in the world. Previously Half-Life's world was something you passed through and other characters interacted with. More specifically, the world was something you watched Alyx Vance interact with. VR necessitated Valve think about the relationship between the player and the world differently, and in turning to Alyx herself they had her nifty tool: the uh, the 'Alyx'. It's a doohicky that allows you to hack Combine terminals and reroute power, which you'll be doing a lot of if you want to upgrade your weapon or disable tripmines. It's satisfying to use: Combine tech really doesn't want to be hacked, and each device has a life - and brain! - of its own that will do its utmost to thwart you.

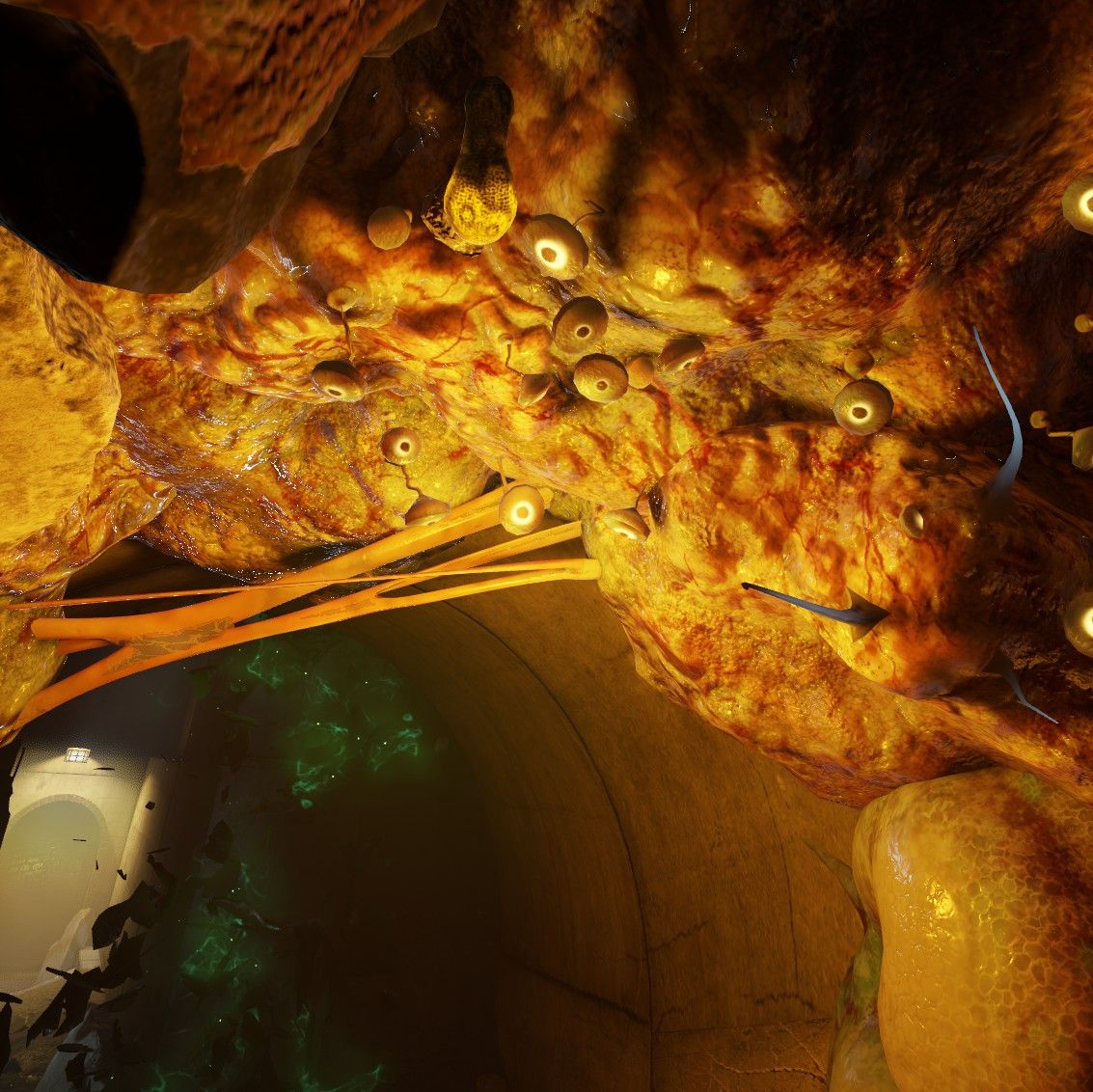

I dunked on the opening settings a bit, but only because their longevity induced fatigue. As environments, they’re absolutely stunning. I was initially lukewarm on the Xenian aesthetics showcased in the trailer as they seemed to be of a drab brown (yeah, yeah, they were various shades of brown in Half-Life, but it’s not 1998 anymore). I needn’t have feared. The Xenian fungus comes in all sorts of shapes, varieties, and colours, and its inclusion makes City 17 feel new again. The often bio-luminescent fungus pulsates, releases spores, and shrinks at your touch. It’d look good in any game, but VR takes it to the next level. It’s so gelatinous, and you can practically feel it.

And then there’s Alyx Vance herself, and with her comes the Half-Life of it all. I again find myself unsure of where to begin, except with her.

THE HALF-LIFE OF IT ALL

Like Half-Life 2 before it, Alyx begins in the shadow of the City 17 Citadel. The cosmic tower, undergoing a complex fortification process that relies on stripping the city of its materials, is a journey for another time. A journey five years in the future, as the game’s opening text informs us, anchoring us in time and space – for the moment at least. Our present journey lies in the opposite direction, to the periphery of the city, where a Combine secret of extraordinary importance is hidden in a territory called the Quarantine Zone.

Alyx herself is a spunky 19-year-old, readily proving herself as both a scientist and researcher vital to the Resistance by following in the footsteps of her inventor father, Eli (James Moses Black). It’s her shoes you inhabit for the game’s duration, and in a first for the series, your character talks. Where Gordon Freeman remained mute to whatever happened to him, Alyx chatters, makes jokes, expresses her fears and concerns, and verbally interacts with the other characters. It’s different, and it does work, but I find the timing of the decision odd. VR is far closer to what Valve were trying to achieve with Freeman in the first place, which is the erosion of the barrier between player and character. VR is such a physical experience, in that you can see and use your hands, and interact in ways that solidify your embodiment of a person in the world. When Alyx speaks, I’m reminded that’s not the case, and I think of her as a person who is distant to me, at which point I begin to reflect on her as a character and not as someone who is representative of me in the world. It’s not a problem. Again, it does work (in so many ways!), and I don’t have strong feelings on whether or not a player’s character should or should not talk, but I can’t help but find Valve’s choice to be dissonant with the methodology they’ve applied in the past and the technology at play here.

But yeah, it works. Really well, actually. The writing (Erik Wolpaw, Jay Pinkerton, & Sean Vanaman) and voice work (Ozioma Akagha, ably stepping in for Merle Dandridge) are pretty great.

We’re regularly reminded that Alyx really is a child of this dystopian world, one whose only memory of Earth is in the dark of the Combine’s malevolent shadow. Throughout the game she’s in contact with scientist pal Russell (Rhys Darby) and whenever she’s nervous, she’ll ask him to talk (alleviating some of our own tension – there are still some moments in which player and character align). Alyx’s questions for Russell here largely revolve around what Earth was like prior to the occupation, and he responds in amusingly idiosyncratic fashion, whether it’s breaking down the club sandwich for her or casually remarking that he downloaded the entire internet before society's collapse. The innocence of Alyx’s questioning, and her range of reactions – awe, incredulity, mocking – reveal a young woman longing for an Earth she’s never seen, but knows from the memories of the kind, gentle, inquisitive minds of those around her.

It’s why when Alyx is asked what she’d like “nudged” – if she were to have a wish, and for that wish to be granted, what would it be? - her answer is earnest and clear: “the Combine off Earth." She repeats it again, in a tone that betrays her youth. It’s a wish made for the good of all humanity, not just for herself, reinforcing our understanding of Alyx Vance as a fundamentally selfless hero.

Unfortunately, the entity posing the question is not interested in selfless actions, and has an altogether different end in mind for Alyx.

IT’S NOT A VAULT. IT’S A PRISON.

When Alyx’s father, Eli, discovered the Combine Vault, he said it contained some kind of “superweapon.” It’s not the most inspiring language to find in a Half-Life game, but I knew Valve would have something far more interesting in mind than some run-the-mill doomsday device. It was just a question of what that would be.

The Combine Vault floats above the Quarantine Zone, huge black wires pulsing with electric green energy draped from its recesses and plugged into sub-stations on the ground. It’s one of Valve’s signature vista-cum-goals, and a stunning one at that. It’s not a stretch to say that the mystery of what the Vault is and what it holds is one of the most satisfying pieces of plotting in the history of the franchise.

At some point prior to the beginning of the story, an unknown entity materialised in a dilapidated apartment block within the Quarantine Zone. It was immediately detected by the Combine, who, acting out of fear, responded with force: they contained the block and built the Vault around it. The sub-stations that hold it aloft contain vortigaunts drained of their powers, but as we’ll learn upon entering the mysterious installation, that's only half of their purpose.

Close to the Vault’s location Alyx overhears a conversation between a mysterious scientist and a Combine Advisor. The scientist’s inclusion is promising, as it points to a new human villain to fill Breen’s vaporised shoes. Honestly, an antagonistic voice was very much missing throughout Alyx. The Combine are our enemy, but without a figurehead like Breen it’s a shapeless threat (rather the point, I know). Our characters – Alyx, Russell, Eli – all get along quite well, and there’s no drama or friction between them. That’s fine, you don’t need to manufacture artificial disagreements, but some level of relatable conflict is needed to give a story real weight.

To digress a little, I actually think this is one of the game’s weaker aspects. Whilst it’s arguably pretty meaty story-wise, there’s a lack of character-centric drama. Too often it relies on the comedic exchanges that take place between Alyx and Russell. Yeah, there’s a ton of golden, laugh-out-loud lines, but somewhere near the end I started to feel the absence of more significant character beats. It’s weird – even when Alyx is in maximum danger beneath the Vault, it’s Russell we hear from, and I kept thinking, “Where’s Eli?" I know the game provides a narrative justification for it – he’s decoding the Combine datapod, give the man some space! – but the ending’s conceit relies on the relationship between father and daughter, and just when the narrative needed to step up and reinforce that, it stuck to the same shtick. Eli and Russell’s roles needed to be switched here. Russell’s great ‘an all, but he doesn’t go anywhere. That’s fine, too, but he feels like an aimless presence in that final sequence, when he really needed to step aside for Eli to take centre stage as the object of Alyx’s affections. I guess I probably have different story priorities to Valve, but that kept jumping out at me at the end, especially with what followed: a lore-shaking revelation that echoed through past, present, and future, built on Alyx and Eli's bond.

Alyx tells a good story, but it resists telling a great one.

As for the scientist lady, I imagine Valve know they need a new human villain, and that’s who they’re setting up for future instalments. Or not (they should).

Anyway! The scientist discusses the Vault’s prisoner in frank terms: “Look, this guy we’ve got in there survived Black Mesa. He raised holy hell then just disappeared.” Our heroes infer from this the Vault contains none other than Gordon Freeman, a superweapon if there ever was one. Alyx is determined to rescue him, calling him, with a small measure of scepticism, “humanity’s saviour." At this stage in the timeline, and with some justification, Gordon Freeman is little more than a myth to Alyx Vance. She assumed him to be long dead, believing humanity is in need of a new hero. It does. It will. But for now, she asks her father what he thinks Gordon’s been up to, and Eli responds with the evasion we’ve come to expect from this character in relationship to that particular mystery. As we know, Eli’s more than aware of what Gordon Freeman’s been up to – or rather hasn’t.

THE FATE OF OUR WORLDS

Alyx succeeds in bringing down the Vault, but as she enters the tractor beam, an urgent message comes through from her father, warning her to go no further. He’s too late. Inside Alyx discovers time and space have been displaced; rooms turned inside out, echoes of a recent past flashing before her eyes (it reminded me a bit of Thief’s ‘The Sword’ and System Shock 2’s ghosts). The Combine attempt to impede her progress, but in a nod to Half-Life 2’s final stretch, the gravity gloves are super charged by the vorts energy, and she makes short (and deeply satisfying) work of her foes.

Beyond, a vast chamber containing a bizarre structure surrounded by floating debris is revealed. At the heart of this structure is a single room occupied by a lone figure. Alyx severs the prison’s power supply, and the structure shatters. “Gordon...Freeman?” she asks, uncertain, even a touch afraid.

She doesn't know it yet, but she has every reason to be afraid.

For the Combine haven’t imprisoned Gordon Freeman. They’ve imprisoned his mysterious employer, the G-Man. And now he is free. The G-Man explains to Alyx that whilst some consider "the fate of our worlds to be inflexible," his “employers” disagree. The G-Man’s job is to “nudge” things in a particular direction. It’s the G-Man who asks Alyx what she’d like nudged, but he declines her request to remove the Combine from Earth. After all, he didn’t go to all that effort at Black Mesa to propel Earth into this cosmic war only to remove it now. The time wasn't right. No, it wasn’t the right moment in time. The G-Man has only one nudge in mind.

Alyx is given a snapshot of the future, and suddenly we’re back where the series left off: five years from now, with Alyx sobbing over the corpse of her father, recently murdered by a Combine Advisor. The G-Man tells her she is seeing the future, and that he will grant her the ability to change it. She takes the chance, destroying the Advisor and saving her father’s life. As ever, it’s a Faustain bargain. The G-Man explains to her that a “recent hire” has proven either unwilling or unable to carry out the tasks set him, and she sees Gordon Freeman in the flesh for the first time. Before she can do anything, Alyx Vance is seized by the G-Man, taking Freeman's place.

But it’s not the Alyx Vance of the present he takes. It’s the Alyx Vance of the future. Our future.

In that future, Gordon Freeman wakes. Eli is alive and the Advisor is dead. Alyx is gone. It hits Eli with force just what the G-Man meant by “unforeseen consequences,” and swears his revenge. “Come on Gordon," Eli says, handing over the crowbar. “We’ve got work to do.”

Well, that’s one way to move the dial on this whole thing. BIG YIKES.

SOMEWHERE IN TIME

I talked in a previous post about how Episode Two was the emotional culmination of Valve’s work in creating a cast of realistic, believable characters you could invest in. The empathetic frontier. Alyx Vance was the heart of that project - the empathetic core that carried us through the narrative. Here’s what I said (what kind of douchenozzle quotes himself?):

It might be that Episode Two’s ending is the ultimate test of the player’s commitment to the world, the logic of empathy taken to its natural conclusion: mourning the murder of Eli Vance at the hands (or tongues) of the Shu’ulathoi. In that ending, we’re not cruelly removed from the action, but left powerless to defend Alyx and her father, and finally immobile in futility as Alyx weeps over his corpse. We can’t reverse this – we can’t prevent the loss of the one thing Alyx held most dear. We care about Eli Vance, but we care about Alyx Vance even more. From the moment Alyx leans over us for the first time, we were always building to an emotional climax in which her grief became our grief. If anything is proof of Half-Life 2's success, it's this.

Earlier in this post, I described Alyx as a selfless hero who puts the needs of humanity before her own. The G-Man’s not interested in that, and he finds the thing that Alyx loves the most - her father - and forces her to make a decision that changes the course of time in a way that benefits her. Well, I say "decision." With the G-Man there's only ever one choice - his choice. The price is her abduction.

There were so many risks for Valve in revisiting Eli’s death and reversing it. It’s a powerful moment they spend a lot of time building up to, and I don’t imagine his resurrection was part of any long term plan. It seems like Valve needed to work their way out of a tricky situation, and this was their answer.

So why does it still work?

Well, it works because of Alyx. The story understands the need for consequences, unforeseen or otherwise, and they’re consequences Alyx has to suffer. Eli’s survival comes at a colossal price, and the intervention fundamentally changes the nature of the Half-Life universe going forward. The G-Man's arc has been moving steadily towards Alyx for some time, and now his interest in her has usurped his interest in Gordon Freeman, which is to say in us (now that we've played as Alyx, where is that line?). Alyx Vance succeeded in preventing her father’s murder, but now she hasn’t lost him so much as he’s lost her. Where once we shared Alyx’s grief over the loss of Eli, we now share Eli’s grief over his loss of Alyx. Inhabiting Alyx for a spell and exploring that relationship away from Gordon Freeman has only solidified that empathetic connection, allowing Valve to perform the switch and make it work. Eli’s relationship with the G-Man has come back to haunt him, and it’s taken what matters most. He tried to shield his daughter from this individual, but she found her own way to him, just like her father.

What this all means going forward is anyone’s guess, and hopefully we won't have to wait a decade and change to find out.

WE’VE GOT WORK TO DO

I liked Half-Life: Alyx so very much. I think it’s an amazing game, in large part because of what it did for the medium. It’s a huge shift in the level of immersion we can experience as players. That's not say I don't still have reservations about VR - the headset is heavy, the experience physically taxing, and I'd still rather sit down at the computer. How long will that remain the case? Hard to say; the problems of VR in 2020 are the same problems it had five, six years ago. But with Alyx, the quality and scale of the content has taken a radical step forward.

It’s also a beautiful, majestic game filled with surprise and invention. Perhaps somewhat selfishly, I was relieved when the game didn’t so much as reverse anything we had planned for our comic but reinforced it. There’s a few details here and there we’ll have to contend with (if we even choose to), but the overarching themes of the game and its expansion of the world dovetailed surprisingly well with what we’ve got planned for New Franklin and the strange dream world to which it’s tethered. It won’t be long before we get to share that, either.

And what of future Half-Life games? I hope there’s more to come in VR – much more – but I also hope the franchise’s future is not exclusively created with that technology in mind. I believe there’s still work to be done with a mouse and keyboard, and I want to see Valve return to that work. For instance, I don’t think Alyx provided a comprehensive answer to the storytelling possibilities of VR. Rather, it only offered glimpses, seen in moments like reaching out for Eli to prevent him falling, or tearing apart the Vault’s power cables with your own hands. Otherwise, it was business as usual, with little you could not do narrative-wise outside of VR. Half-Life: Alyx even took a step back from the previous games in a crucial respect, with few scenes involving characters in your presence. Given this was one of the hallmarks of the series, its absence was noticeable here.

That being said, if they do produce a new title outside of VR, there are many things that won’t be the same, nor should they be. Alyx’s combat was superlative, and I hope whatever lessons Valve learned there can be transferred to future games. The ability to upgrade weapons in meaningful ways was super fun - can we ever forget resin? - and that seems like something that should be carried over. The increased interactivity with the world was an improvement on previous games, and I’d like to see more of it, please.

Above all else, though, I’d like to leave City 17. I’d had enough of it come Episode One, and I never imagined being enticed back. Much to my surprise, I was glad to return in Alyx, and it never felt like a retread of a world we’ve seen several times before. But I don’t think you can repeat that again, and by the time Alyx drew to a close, I found myself again wishing to leave it behind. The episodic trilogy promised an adventure beyond City 17, and we only saw half of that promise. I don’t much care where we go or what we do, but it needs to be fresh, exciting, and new.

Fortunately, it looks like that's just what we're getting. Half-Life: Alyx is many things, and one of them is a statement: Half-Life is back, and there's more to come.

Should be fun.

Thanks for reading.