A New Kind of Protagonist

The way Albert Kempinski tells it, you’d think he was the only victim of the planet-wide catastrophe known to the world of Half-Life as the Black Mesa Incident. Kempinski is so consumed by grief and loss that he has blinded himself to a most pertinent existential truth: in the world of Half-Life, every living person is bound together by the same calamity. Everyone lost something or someone or both, everyone’s life was upended. The rest are dead. There is precious little humanity left.

This insular, self-absorbed perspective was our way into the psychological makeup of our new protagonist.

The question as to how an ordinary person dealt with the implications of global devastation and alien invasion formed the basis of our initial thinking for the character. Almost without exception, the principal characters of Half-Life 2 are united by their direct involvement in the Black Mesa Incident. And that makes sense! So much of the series is about guilty scientists trying to right their wrongs by defending humanity from the terrors they accidentally unleashed upon an unsuspecting and woefully under-equipped world. And at the root of it all, there’s you, the player; you created this world, and now you must put it back together again.

That’s Half-Life.

From left to right: Isaac Kleiner, Eli Vance and Alyx Vance.

And this being Half-Life, at least one of our protagonists had to be a scientist as well (but not of Black Mesa!). Leyla, conceived as a rational, idealistic voice in a sinister world, neatly ticked that box. The vortigaunt Dreyfus let us see the story from an alien perspective, but by virtue of being a vortigaunt he was closely aligned with the mythology of the world. Our ordinary joe, on the other hand, had to come from a place far removed from the tropes of the series, a person whose life experiences were unlike anything we’d seen in the universe so far.

One of the best ways to do that was to filter the Half-Life experience through their perspective. What does Albert Kempinski think of Black Mesa? Not a lot, it turns out. He blames it for taking away “everything” he had, and that’s a question we’ll get into as the story moves forward. But the larger implications of Black Mesa have been seized by him, too. As we learn in Chapter 1, he’s now contemptuous of the entire scientific enterprise; for him, the values Half-Life holds dear – the wonderment of knowledge, the genius of scientific innovation, of rational minds triumphing over totalitarian terror – are in essence corrupt. And as we dig deeper into the world of New Franklin, you’ll see that he’s found a society that has woven distrust and fear of science into its politics, its civilian life, its entire reason for being.

Gabe Newell once remarked that the conflict between Gordon Freeman and Doctor Breen would be judged by which of them was the better scientist. Breen, being the game’s villain, naturally comes down on the losing side; he’s self-seeking and vain, whereas Freeman uses the gift of intellectual reason to topple an alien police state. We see that Breen’s science is cold and self-serving, whilst the resistance’s is compassionate and giving (delivered at the sharp end of a crowbar, of course). But for us going into the Half-Life universe, it made sense that to someone like Albert Kempinski, Freeman and Breen were essentially the same problem, the same root cause of all this misery.

That...felt like a very compelling way to go about constructing the narrative. That, of course, being a character who vigorously rejected the world of Half-Life.

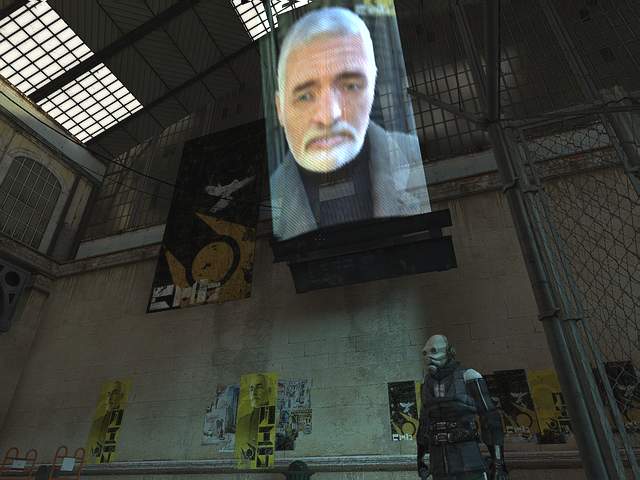

“I am reminded at times like these that our true enemy is instinct.”

Compassionate science at work.

On the surface of things, telling a post-apocalyptic story from the perspective of an average citizen is something of a cliché, even when taking into account the nuances and peculiarities of Half-Life. There’s nothing groundbreaking about that approach. But we recognised that and embraced it; for better or for worse, that’s where we had to begin.

And so, Albert Kempinski’s introduction in the first chapter hits a lot of familiar beats. He’s morose and cynical, dwelling on the loss of his wife, a picture of whom he keeps in his wallet to remind him of better days. The comic’s action begins with the abduction of his daughter, forcing him to leave his isolation and rescue her. It’s a basic set-up, and one that amply serves the demands of the opening chapter.

Concept art of Kempinski.

In order to deconstruct Kempinski’s archetype, it was important to paint its broad strokes at the beginning. That had its risks, but given the payoff we had in mind, we felt secure taking them (we shall see in due course if we were able to pull it off...!).

Then we’d work backwards. So, one of the decisions we made very early on is that we wanted to tell Kempinski’s past in reverse chronological order. We wanted to serve the reader with a character they felt they understood intuitively, and then gradually unravel that. A parent trying to rescue their imperilled child is something we just get on an empathetic level. And so, that’s why we’re introduced to him on the night of her kidnapping, and go into the details and circumstances surrounding it.

But what happens when the parent is conflicted about that? We could throw all kinds of obstacles in Kempinski’s way – and we do! - but for us real the obstacle between Kempinski and rescue was always going to be himself. We wanted a character whose relationship to his child was so strained, so adversely impacted by the world’s predicament that he would question the very point of rescuing her. And if he were, let’s say, unable to find a satisfying answer to that question, what would he have to do to make it worthwhile? What lengths would the character go to to change the circumstances of the world around him?

It’s these questions that guided us as we crafted Albert Kempinski. As the series progresses, we’ll go further and further back in time, and hopefully, if we’re successful, you’ll find the revelations they hold challenge and contradict the notions you’ve already formed about who Kempinski is and what he wants.

And whilst I’d love to talk more specifically about the man himself, that would inevitably entail venturing into spoiler territory! I hope this small, discursive piece has proven at least somewhat interesting, and I look forward to talking more about it as we go on.